QuantaDose Press Releases

Metal Rain from the Skies: The First Direct Proof That Reentering Rockets Are Peppering Earth’s Upper Atmosphere with Metal Pollution

On the cold early morning of February 19, 2025, a tumbling Falcon 9 upper stage blazed across European skies in a spectacular uncontrolled reentry. Observers from Ireland to Poland captured long-exposure photos of glowing streaks and fireballs lighting up the night. Most people saw a beautiful light show. A small team of atmospheric physicists in northern Germany saw something else entirely: the first-ever direct measurement of human-made metal pollution injected high into our planet’s atmosphere by space debris.

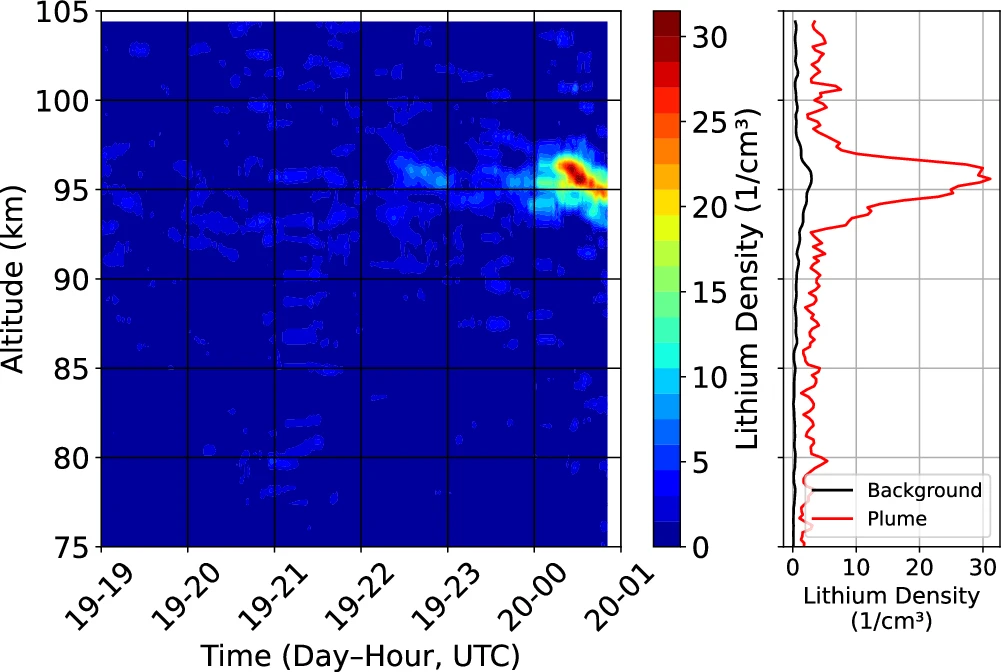

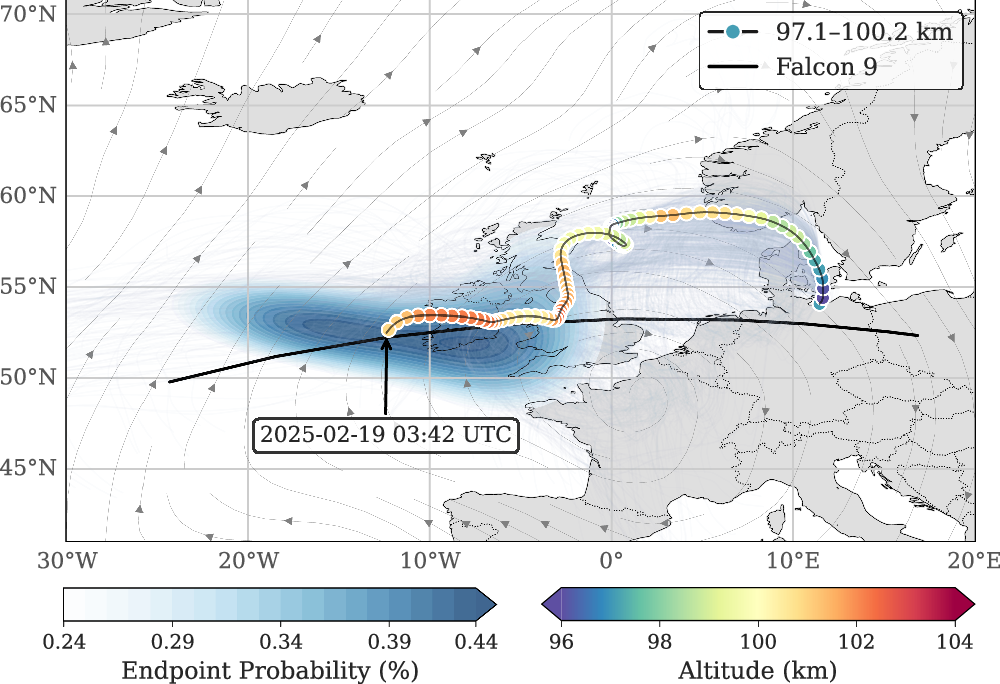

Less than 20 hours later, their resonance lidar instrument at Kühlungsborn detected a sharp, drifting plume of lithium atoms at 96 km altitude — exactly 10 times the normal background level. They traced the plume 1,600 km back to the rocket’s reentry path west of Ireland. The study, published today (February 19, 2026) in Communications Earth & Environment (a Nature journal), marks a historic milestone: the first time scientists have directly observed and fingerprinted upper-atmospheric pollution from a specific spacecraft reentry.

This isn’t just one dramatic event. It’s a glimpse into a growing, largely unregulated form of atmospheric pollution that comes from the very success of the modern space age.

What Actually Happens When a Rocket Stage or Satellite Reenters?

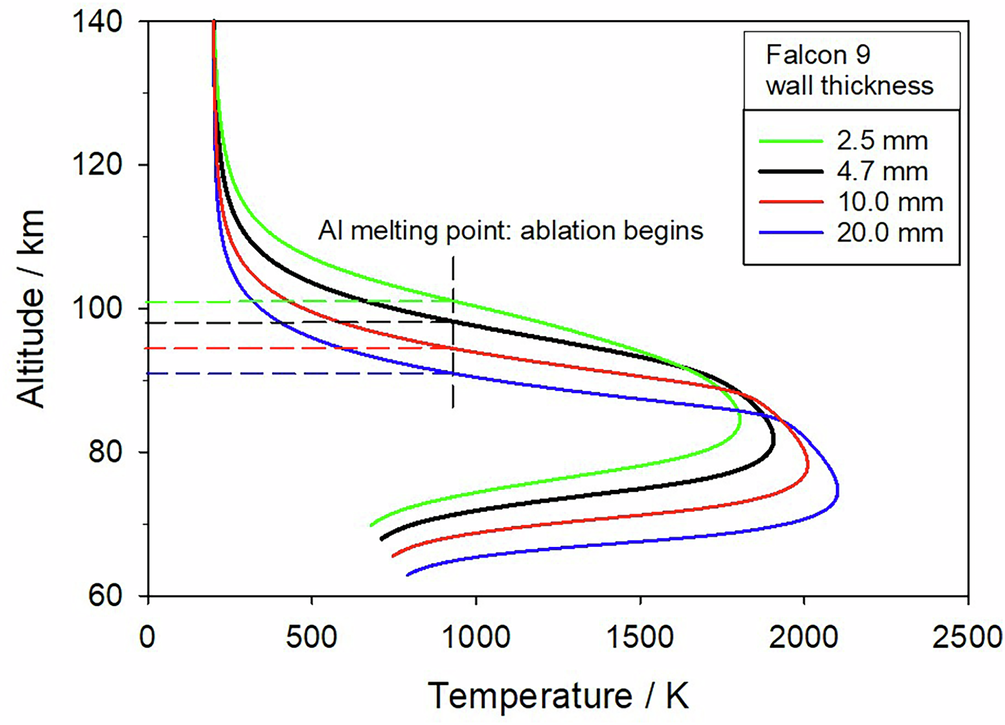

Spacecraft don’t “fall” cleanly to the ground. As they plunge through the mesosphere and lower thermosphere (roughly 80–120 km altitude), friction heats them to thousands of degrees. Materials vaporize layer by layer — a process called ablation. The metals turn into atomic vapor, then rapidly oxidize or condense into tiny nanoparticles that drift with the winds.

For this Falcon 9 upper stage (a 3.9-ton aluminum-lithium alloy structure with lithium-ion batteries), scientists estimate about 30 kilograms of lithium alone was available to vaporize. That’s roughly 375,000 times the entire daily global input of lithium from natural meteoroids (~80 grams per day worldwide).

The lidar caught the atomic lithium before most of it oxidized. The plume sat between 94.5 and 96.8 km, peaked at 96.1 km, and was visible in the data for roughly 27–40 minutes as it drifted overhead.

Every Element Scientists Have Linked to Spacecraft Reentries

The 2026 study focused on lithium because it’s an excellent tracer: extremely rare in natural meteoroids but deliberately used in modern spacecraft alloys and batteries. But lithium is only the tip of the metallic iceberg.

From direct stratospheric sampling (the 2023 NOAA SABRE mission) and modeling of spacecraft composition, researchers have now identified more than 20 elements injected by reentries that either exceed natural cosmic-dust levels or appear in ratios that scream “engineered alloy.”

Primary anthropogenic tracers (mass input already exceeds natural meteoric input):

- Lithium (Li) — ~30 kg per Falcon 9 upper stage. Ablates high (~98 km). Atomic form lasts hours before oxidizing. Low direct toxicity (used in medicine, but excess affects kidneys/thyroid). Net effect: excellent tracer; adds to overall metal loading.

- Aluminum (Al) — dominant structural metal (often 70–90% of satellite/rocket mass). Forms Al₂O₃ (alumina) nanoparticles. Ablates ~90–110 km. Particles can persist 1–5+ years once they reach the stratosphere. Low acute toxicity; chronic high exposure is debated for neuro effects. Net effect: alters aerosol microphysics, radiative balance, and can heat the mesosphere (models show up to ~1.5 °C in high-reentry scenarios).

- Copper (Cu) — wiring, engines, heat shields. Exceeds natural input. Moderate toxicity in excess (liver/kidney). Net effect: contributes to new particle surfaces.

- Lead (Pb) — solders, shielding. Highly toxic neurodevelopmental hazard with no safe exposure level. Atmospheric flux from reentries still tiny compared to legacy ground pollution. Net effect: adds to metal nanoparticle mix.

Other confirmed spacecraft-derived metals (rare or absent in natural meteors):

- Titanium (Ti), Niobium (Nb), Hafnium (Hf), Molybdenum (Mo), Silver (Ag), Tin (Sn), Beryllium (Be), Chromium (Cr), Nickel (Ni), Zinc (Zn)

These appear in stratospheric sulfuric-acid particles in ratios matching aerospace alloys. About 10% of large stratospheric aerosols already contain them. With planned mega-constellations, that fraction could reach 40–50% within two decades.

How Long Do These Metals Stick Around?

- Atomic vapor phase (what the lidar saw): Short-lived. Lithium atoms oxidize below ~95 km or ionize above ~100 km. The detectable plume lasted tens of minutes locally and dispersed over ~20 hours of advection.

- Oxide nanoparticles (the long-term form): These are the real players. Tiny alumina and mixed-metal particles are transported poleward and downward by the global circulation. Recent whole-atmosphere models show they can reach the stratosphere in 1–3 years (much faster than older estimates of decades). Once there, stratospheric aerosols typically reside several years before slowly sedimenting.

- Cumulative buildup: With thousands of satellites and rocket stages reentering annually, the middle atmosphere is shifting from “pristine, meteor-dominated” to “increasingly anthropogenic-metal-influenced.”

These metals and their oxides would not exist in these quantities or ratios naturally at 90–100 km. Meteoroids deliver chondritic material with very different composition. Spacecraft deliver engineered, high-performance alloys — a completely new chemical fingerprint in a region that was previously one of the cleanest on (or above) Earth.

Human Toxicity: Not a Direct Threat, But Worth Watching

Because the pollution occurs so high up and is extremely dilute by the time any material reaches the troposphere, direct human exposure is negligible. You’re not going to inhale rocket lithium or lead from the sky in meaningful amounts.

Quick reference table:

| Element | Typical Human Toxicity Profile | Atmospheric Context Concern |

|---|---|---|

| Lithium | Low–moderate; therapeutic uses but overdose toxic to kidneys/thyroid/neurology | Tracer only; minimal direct risk |

| Aluminum | Low acute; chronic high exposure debated neuro link | Main volume; chemistry/radiative effects dominate |

| Copper | Essential trace element; excess causes GI upset | Low risk at these fluxes |

| Lead | Serious neurotoxin; developmental harm; no safe level | Lowest volume but highest per-atom concern if fluxes grow |

The real story is not ground-level poisoning — it’s what these novel particles do while they’re floating in the upper atmosphere for months to years.

Net Effects on the Upper Atmosphere: The Big Unknowns

The mesosphere and lower thermosphere have always received a gentle drizzle of cosmic dust. Now we’re adding a growing industrial-scale sprinkle of metals in unnatural ratios. Researchers are clear: we don’t yet know the full consequences, but there are “enough reasons for concern” to study it urgently.

Known or modeled effects include:

- Radiative and thermal changes: Alumina nanoparticles can absorb and scatter light differently than natural meteoric smoke. High-reentry scenarios project measurable warming (up to 1.5 °C) in parts of the mesosphere and shifts in polar vortex strength and stratospheric winds.

- Aerosol microphysics: New particles change the size distribution, number, and surface area of stratospheric aerosols. About 10% are already affected; future projections suggest this layer could look quite different.

- Heterogeneous chemistry: The extra surfaces provided by metal oxides can host reactions that wouldn’t happen on natural particles alone — potentially influencing trace-gas cycles and cloud nucleation (including noctilucent clouds higher up).

- Cumulative loading: One Falcon 9 is a blip. But with Starlink-scale constellations (thousands of satellites with ~5-year lifetimes), annual reentry metal mass could rival or exceed natural meteoric input for several elements. That changes the baseline chemistry of the entire middle atmosphere.

The 2026 study authors emphasize: “There are many elements present inside spacecraft which are not very present in our atmosphere due to natural causes. We know very little about what metals actually exist in the atmosphere and how that relates to re-entry pollution.”

Why This Matters in the Era of Mega-Constellations

We are living through the fastest growth in orbital objects in history. Thousands of new satellites launch every year. Most will deorbit and burn up within 5–10 years by design — the responsible way to avoid orbital debris. But that “responsible” choice now means deliberately injecting engineered metals into the upper atmosphere.

This is an uncontrolled global experiment on the pristine layers above 80 km. The first direct measurement just happened. The next steps must be systematic long-term monitoring, better ablation models, and — crucially — international discussion about what materials we send to space and how we bring them back.

Researchers are calling for expanded lidar networks, more high-altitude aircraft sampling, and whole-atmosphere chemistry-climate modeling that includes reentry emissions. Some are even exploring design changes: satellites that minimize high-ablation metals or controlled reentries that target less sensitive atmospheric regions.

Looking Up — and Thinking Ahead

The same technology that lets us stream internet from orbit, monitor climate change from space, and explore the solar system is now leaving a metallic signature in the air we breathe… indirectly, through complex atmospheric transport.

The February 2025 Falcon 9 event was dramatic and visible. The invisible plume it left behind was far more significant: proof that humanity’s reach into space is now altering the thin envelope of gas that protects and sustains all life on Earth.

We don’t need to panic. We do need to pay attention — and start treating the upper atmosphere with the same care we now give the stratosphere (post-Montreal Protocol) and the troposphere (clean-air laws).

The sky isn’t falling. But pieces of our rockets are, and they’re leaving something behind. The age of space sustainability isn’t just about avoiding collisions in orbit — it’s about keeping the air above us as pristine as the view from space.

What do you think? Should we design satellites differently? Regulate reentry materials? Or is this an acceptable trade-off for the benefits of mega-constellations? The conversation starts now — because the measurements have finally begun.

Sources: Wing et al. (2026) Communications Earth & Environment; Murphy et al. (2023) PNAS SABRE study; supporting modeling papers 2024–2025. All data current as of February 2026.

Let me know if you’d like references expanded, a printable PDF version, or a follow-up deep dive on any specific metal or modeling study! The upper atmosphere just got a lot more interesting.

The article (and the Nature study it reports on, published Feb 20, 2026) specifically highlights lithium as the detected pollutant from the Falcon 9 upper-stage reentry, while referencing aluminum (from Li-Al alloys) and citing prior studies on lithium, aluminum, copper, and lead as metals now exceeding natural cosmic-dust inputs. It also notes “other metals” and “many elements present inside spacecraft” not abundant naturally in the upper atmosphere.

Here’s the complete list of explicitly mentioned elements being deposited via spacecraft reentry/ablation:

- Lithium (Li) — primary focus of this detection (tracer because it’s rare naturally).

- Aluminum (Al) — main structural metal in spacecraft (Li-Al alloys, etc.).

- Copper (Cu) — from prior studies on reentry pollution.

- Lead (Pb) — from prior studies on reentry pollution.

Broader context from the referenced 2023 PNAS/NOAA SABRE study (and Nature paper’s discussion): Over 20 metals total have been detected in stratospheric aerosols from reentries, including titanium (Ti), niobium (Nb), hafnium (Hf), silver (Ag), tin (Sn), etc. But the user-provided text sticks to the four above plus vague “other metals.”

Deposition Height

Ablation (vaporization) of these metals occurs mainly in the upper mesosphere / lower thermosphere, ~80–120 km altitude (peak ablation often ~90–100 km).

- Specific to this event: Lithium plume detected at 94.5–96.8 km (peak 96.1 km), ~20 hours after reentry at ~100 km west of Ireland.

- This matches typical spacecraft reentry ablation layers (similar to meteor ablation, but with different metal ratios/composition).

These metals would not be present in these quantities or ratios naturally at those heights. Natural input comes almost entirely from cosmic dust/meteor ablation (~80 g/day global lithium from chondritic meteoroids; spacecraft can inject ~30 kg lithium from one Falcon 9 upper stage alone). Spacecraft alloys introduce “exotic” engineered compositions (high Li, specific Al alloys, elevated Cu/Pb relative to meteors).

How Long They Stay in the Atmosphere

- Atomic form (as detected for lithium): Transient — the plume was observed for ~27–40 minutes locally; the cloud advected ~1,600 km in ~20 hours. Lithium atoms oxidize quickly below ~95 km (to LiO/LiO₂) or ionize above ~100 km.

- Overall (vapors → compounds/particles): Metal vapors rapidly oxidize and condense into nanoparticles (e.g., Al₂O₃, metal oxides). These descend via circulation (poleward/downwelling in winter mesosphere) and reach the stratosphere in models estimate 1–3 years (some older models said up to 30 years, but recent ones with realistic transport are shorter). Once in the stratosphere, aerosols reside several years before sedimenting further.

- Cumulative effect: With rising reentry rates (mega-constellations), metals accumulate and persist for years/decades in the middle atmosphere.

Toxicity Levels to Humans

Direct human exposure/toxicity from these upper-atmospheric deposits is negligible — they’re extremely dilute, at 90+ km altitude, and most eventually reach the ground in tiny fluxes (far below tropospheric pollution sources). Concerns are indirect (atmospheric chemistry changes) rather than inhalation/ingestion.

| Element | Toxicity Profile (Human) | Notes on Atmospheric Context |

|---|---|---|

| Lithium (Li) | Low environmental toxicity overall; does not bioaccumulate significantly. High doses (e.g., from meds or industrial) can cause kidney damage, thyroid disruption, neurological effects. | Considered low-risk; used therapeutically but overdose-toxic. Atmospheric atomic/oxide forms not a direct exposure route. |

| Aluminum (Al) | Low acute toxicity; chronic high exposure linked to possible neurotoxicity (debated). | Common in environment; atmospheric nanoparticles mainly a chemistry concern, not direct health. |

| Copper (Cu) | Essential trace element; excess causes liver/kidney irritation, gastrointestinal issues. | Toxic in high occupational exposure; atmospheric contribution tiny vs. other sources. |

| Lead (Pb) | Highly toxic — neurotoxin, developmental harm, no safe exposure level (affects brain, kidneys, blood). | Most concerning if it reached ground in quantity, but reentry fluxes are small globally (<2 tons/year vs. hundreds from legacy pollution). |

Net Effects in the Upper Atmosphere + Interactions with Chlorine (CFCs)

These additions alter the natural chemical composition of the mesosphere/lower thermosphere and eventually the stratosphere. Natural meteor input is “background”; spacecraft add excess mass + unnatural ratios, creating novel chemistry.

Key net effects (per the Nature study and supporting research):

- Ozone depletion risk (main concern): Aluminum rapidly forms Al₂O₃ (alumina) nanoparticles. These act as surfaces for heterogeneous chemistry, activating reservoir chlorine (HCl/ClONO₂ from legacy CFCs/halons, which are still present though declining post-Montreal Protocol). This converts inactive chlorine into active ClOₓ that catalytically destroys ozone — similar to how polar stratospheric clouds (PSCs) work, but potentially more widespread. Transition metals (Cu, Ti, etc.) may have catalytic roles too. Result: Could slow ozone recovery or cause small additional global/seasonal losses (models show concern for mega-constellations injecting hundreds of tons of Al₂O₃/year).

- Radiative/climate effects: Metal oxides can absorb/scatter radiation, slightly warm the mesosphere, alter winds/temperatures, or change aerosol microphysics (new particle formation, size distributions).

- Aerosol/cloud nucleation: May influence mesospheric/stratospheric clouds (e.g., polar mesospheric clouds, PSCs), affecting radiative balance.

- Lithium-specific: Mostly a tracer here; less direct catalytic impact than Al, but adds to overall metal loading.

- Overall uncertainty: Article/study emphasize “enough reason for concern” but “more research needed.” Cumulative reentries could make reentry metals 40%+ of total meteoric mass flux in coming decades, with unknown long-term perturbations to ozone, climate, and high-altitude chemistry.

Specific to your chlorine/CFC question: Yes — the interaction is exactly analogous to the original CFC problem. CFCs released chlorine that destroys ozone; banned CFCs are declining, but remaining stratospheric chlorine reservoir can be “unlocked” more efficiently by new surfaces from Al₂O₃ (and other metal oxides) from reentries. This is why studies flag it as potentially counteracting Montreal Protocol gains. (Rocket launches themselves also emit some chlorine/soot, but reentries are the bigger emerging issue for metals.)

In short: This is a new, growing anthropogenic pollution source in a pristine atmospheric layer. One Falcon 9 event produced a clear, traceable lithium plume; scaled up, the aluminum-driven ozone risk is the biggest flagged concern. The field is very young (this is the first direct lidar detection), so implications are still being quantified, but the consensus is we should monitor closely as launch/reentry rates rise.